Staples History must be part of any Climate ‘Stocktake’

How to avoid the pitfalls of past energy transitions

On the recent release of the United Nations’ first ‘global stocktake’ of climate-destablising fossil-fuel emissions since the COP21 Paris agreement in 2015, the UN called for ‘radical decarbonisation’ with a fast phase out of fossil fuels. This UN climate stocktake aims to put governments under pressure to dramatically ramp up their emissions reduction plans. It will shape discussions at the COP28 global climate talks to be held in Dubai later this year.

Historically energy transitions, such as that from animate prime movers, human muscle, wind (sail) and water (mill) to the hydrocarbons of coal, gas and oil, have taken 50-75 years. As any of us living through 2023 - the hottest year in 120,000 years - knows, we just don’t have that time. We have crossed 6 of 9 planetary boundaries and the planet is 'well outside the safe operating space for humanity'. Can we learn from the transitions of the past to avoid further delays and obstructions? Part of any stocktake has to reference history, in this case, that of energy transitions in what we might call Staples History.

In the energy transitions the globe has already undergone there are surprisingly overlaps, hesitations, even intensifications of previous energy sources. Transitions were highly localised, contingent on available resources and trade routes. They were also critically decided, and sometimes hampered, by markets, labour exploitation and protection from competition. This current transition is no less market driven.

***

Pre-industrial cities of half-million populations relied on proximate wooded areas 50-150 times larger than their own footprint. There was also widespread deforestation around the furnace sites for the smelting of metals using charcoal. But in British colonies such as New South Wales and its District of Port Phillip (Victoria in 1851) deforestation facilitated the clearing of runs for pasture and crops. In these locales wood seemed boundless and it was gratis and expendable, rather than costing biodiversity dearly and causing zoonotic viral transfers to humans. And of course, it was not just trees being ‘cleared’ for pasture and crops, but the sovereign peoples who had managed those forests and depended on them for their livelihoods and who were emplaced within them through kinship networks.

For all the emphasis on industrialisation, the phytomass fuels of wood and charcoal, the biomass of crop residues, dried dung, along with water and wind still dominated up until 1880. They were cheaper. Some nations still depended on phytomass (wood and charcoal) throughout the twentieth century just as others were shifting from coal to oil. As with renewables today, the bolting horse must be securely saddled by profit to supersede entrenched sources. For example, in New England in 1850 steam was three times more expensive as a prime mover than water (in textile mills). Energy historian Vaclav Smil finds industrial waterwheels and turbines ‘competed successfully with steam engines for decades’.

Andreas Malm argues that the real impetus for steam powered factories was concentrating and pacifying workers in urban manufacturing centres. Strikes and machine breaking were also expensive. Certainly, if governments are still as cowed by the demands of the corporations who lobby and fund them we will not achieve a ‘just transition’ for workers, if anyone, anytime soon.

In North America coal did not surpass wood consumption until as late as 1884, as crude oil became more important. Curiously North America’s impetus towards oil was to find a replacement for expensive and incredibly gruelling to acquire sperm oil (rather than coal) with the US peaking at 700 whaling vessels in 1846. It was mostly used as a lubricant and in limited lighting. Crude oil was struck first in Pennsylvania in 1859. To extract it required drilling down 21 metres and the drill was powered by a steam engine – which may have been fired by wood. The head laterns of miners were likely lit by whale oil. So many energy overlaps.

When energy historians refer vaguely to ‘human muscle’ they do not specify slavery, or forced labour such as convict transportation and indenture. These gross disparities of exploitation and wealth need to inform the current energy transition too, such as migrant gig workers labouring in intensifying heat. Employers are supplying them with ice-vests, reminiscent of coal shovelers in the stokeholes of steam ships who were immersed in ice-baths on collapse, as On Barak documents.

Coal effectively ‘speeded up’ extant proto-industrial sectors such as textile and print production and traditional manufacturing. Yet it did not bring about the expected involution of human labour. Early coal mining in fact increased the demand for human labour, sometimes for boys as young as 6yrs for lighter tasks. Conditions were generally horrific.

Industrial relations are deciders in any energy transition. To achieve this one in time we need to apprentice for renewable skills and transition existing coal-fired plants and their workers, collect renewables into the grid with new transmission infrastructure and create a renewable storage target. There's certainly no shortage of work to do in an energy transition.

The current transition to renewables is no less hindered by demands for 'business certainty'. The Albanese Government is committed to a ‘just transition’ and job security for workers, yet it also seems cowed by the demands of the corporations who lobby and fund them. Climate scientist Joëlle Gergis points to $11.1 billion in subsidies and tax breaks gifted to 'the culprits squarely responsible for ushering in this new era of "global boiling"‘.

***

We should also remember that coal was hardly new. The English had used it for domestic heating from the time of the Romans because it burned longer and was nearly double the energy intensity of wood. In China the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) used coal in iron smelting. Belgium first extracted coal as early as 1113 and were shipping to London in 1228. The English exported from the Tynemouth region to France from 1325. It was endemic deforestation that necessitated Britain’s shift from phyto/biomass to coal in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The majority of England’s coal pits opened between 1540 and 1640.

Coal also produced machinery (forging iron and steel) and fertilizers, tools and implements. It pumped water from deepening mining pits and transported agricultural produce, including the huge amount of feed concentrate needed for working animals. In the 1820s naval steam-engines were introduced. Yet for all this take-up coal powered quite limited industries - textile, print, transportation and iron smelting – and only fully after 1840 by which time coal had still only reached 5% of the global market.

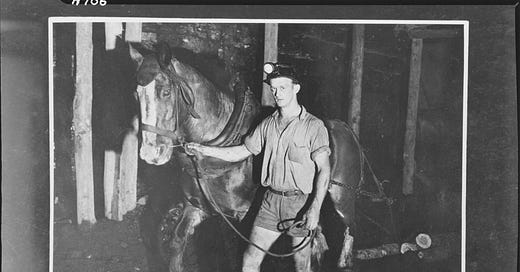

Transportation was critical to this ‘industrial revolution’. Animate prime movers provided 87% of world power in 1800, but persisted to 27% of that power till 1900. The energy of draft livestock came mostly from horses who had gradually been replacing oxen after the introduction of the collar harness. Globally horses were still the predominate prime mover until the mid-twentieth century. Coal was often raised from pits by draft horses harnessed to beams fastened to axles - the deployment of horses with coal extraction was thus expanded. Smil shows, ‘every transition to a new energy supply has to be powered by the intensive deployment of existing energies and prime movers’. He concludes the term ‘industrial revolution’ is ‘misleading’ since its advance was ‘gradual, often uneven’.

The exploitation of animals under the current high-tech transition hardly seems relevant. Yet another historical shift in the exploitation of animals from prime-movers to food has lessons. Intensive animal farming and livestock production accounts for 18-25 per cent of the world's GHG emissions, from land-clearing to refrigerated transport. In unexpected ways, human relations to these 75 billion animals who are slaughtered annually – no less sentient than our beloved pets – continues to be a critical point for emission reductions.

Coal powered steam ships, driven by the screw propeller, transported the majority of 60 million emigrants from Europe between 1815 and 1930, including many to Australia. And from the 1830s locomotive engines, even if they burned wood (half as efficient as coal), required forged steel tracks. Coal itself had to be transported, and in a feedback loop, powered transportation.

Efficiencies are critically important in the uptake of new energy sources. In their early incarnations steam engines were only converting 2% of coal into useful energy and no more than 15% utility was surpassed even up until 1860. Despite modifications and improvements after the much-anticipated expiry of James Watt’s patent, steam engines remained highly inefficient with steam locomotives wasting 92% of the coal stoked into their boilers all the way up until 1900. Even today, petrol-powered cars still waste about 66% of the energy in their fuel.

In the contemporary context carbon capture & storage is similarly extolled as a great enabler of transitioning, when in reality it is highly inefficient and unproven, currently capturing 1 percent of emissions. Our decisions need to be evidence-based, not market expedient, in the uptake of technologies to cut emissions. Carbon offsetting is similarly proving to be ineffective, yet much promoted, precisely because it provides a greenwash over fossil fuel’s actual refusal to transition away from fossil fuels.

***

The nineteenth century was a complex energy transition in fact decades long, from global consumption levels in its commencement of 20EJ, 98% of which was phytomass. By the end of this century energy supply had doubled and half of it was from coal. Yet Britain’s coal extraction peaked as early as 1913 then underwent the ‘transitions’ from steam engines to internal combustion engines, followed by steam turbines, then gas turbines.

At the COP28 in Dubai nations will have to grapple with the long shadow of past energy transitions marked by asymmetrical structures of trade, transfer and exchange in order to effect the current transition to renewables. The negotiations will have to take into account the exclusion of poor countries from global commodity circuits and the mineral extractions that renewables depend on from what are now called ‘Super Regions’ (once called ‘Colonies’).

In stabilising our climate we need to also stocktake from the mistakes of past energy transitions. From Staples History we might learn from the legacies of past energy transitions, such as child labour, coerced and non-union labour, colonial extraction, dispossession and intergenerational impoverishment, animal exploitation and cruelty. Surely we can avoid the misery inflicted by past resource extraction if energy history alerts us to their literal pitfalls.

I find the Greens in Australia - particularly in VIC - a combination of technophobic neo-Luddites, ferals, NIMBYs and disguised Trots.

As shown in 2019 in the UK with Corbyn, very few voters are interested in a return to dead socialism.

Back in July, the Tories narrowly retained the London suburban seat vacated by the disgraced Boris Johnson, even though it had the smallest margin of the three. They did this by exploiting opposition to the plan by the Labour mayor of London to extend the ultra-low emissions zone (ULEZ) to the whole of Greater London.

ULEZ is a tax on high-emission vehicles, designed to cut London's CO2 emissions. The plan has operated successfully in central London (where most people use public transport) since 2015, but its extension to the commuter belt (where most people drive to work) has met fierce opposition.

Of itself, this small Tory success is of no significance - Rishi Sunak's ramshackle government is still headed for a heavy defeat at the 2024 election. But it sends a very bad signal.

All of Europe is currently being given a graphic illustration of the reality of climate change, in the form of a second successive summer of lethal heatwaves. (June was the hottest month ever recorded in the UK.) Yet voters in suburban London still voted to put their right to run high-emission cars ahead of all other issues.

This underlines how difficult it is proving to be to get public acceptance for the much more radical changes that will be necessary if the rapidly approaching climate apocalypse is to be averted, or even mitigated.